Dominique Morisseau is a “meat and potatoes” playwright in the best sense of the term. She doesn’t want her audience to leave her plays without getting a full dramatic experience. In “Bad Kreyól” she takes us to Port-au-Prince, Haiti through the eyes of her protagonist Simone (Kelly McCreary), a conflicted American idealist who has come to Haiti with a dual mission of helping the desperate and helping herself come to terms with the legacy of her Haitian ancestry.

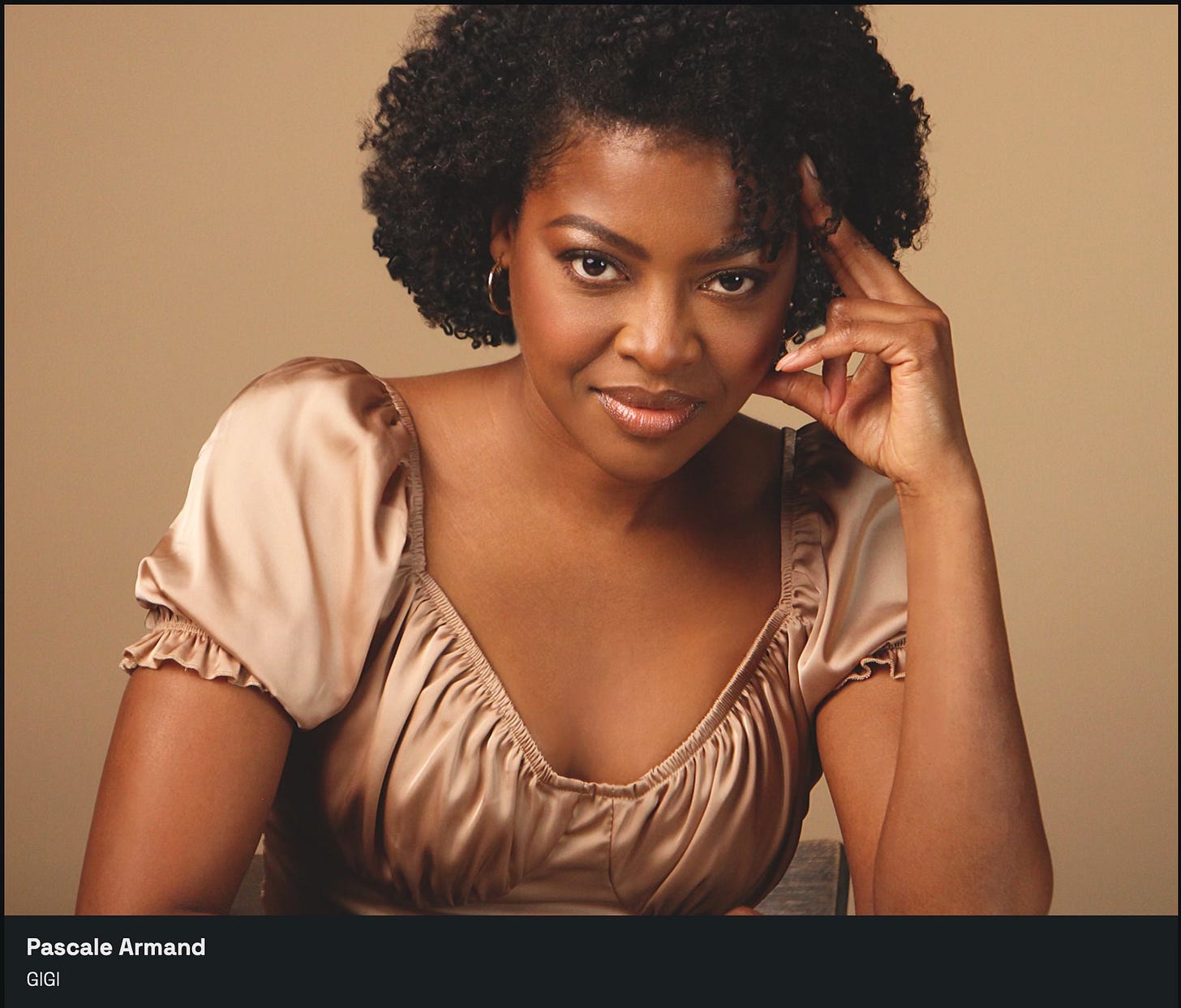

Simone’s mission of aid to Port-au-Prince’s residents gets her involved in two intertwining stories and lives. The first involves her cousin Gigi (Pascale Armand), a tough, single-minded woman who runs a successful clothing boutique near the beach. Gigi may be implicated in the exploitation of women working in the clothing industry, and Simone wants to find out the truth.

The second life Simone inserts herself and her good intentions into is Gigi’s gay male servant, Pita (Jude Tibeau). Pita is a “Restavek,” a kind of foster child that in Haiti amounts to a lifetime of indentured servitude. Pita is gloriously flamboyant and part of the sparkle that makes the magic happen in Gigi’s boutique. Simone encourages Pita to organize for LGBT rights with a predictably dangerous outcome. The play questions these urges on Simone’s part to help those she considers in need. Is her philanthropy selfish rather than selfless, is it just another form of colonialism?

Yet the real pleasure of watching Morisseau’s play is not in following Simone’s befuddled efforts to help others which leads her to an inevitable comeuppance and finally to a resolution that is both touching and elegantly balanced. The center of Morisseau’s play is the strange, sibling-like relationship between Gigi and Pita and the way they take care of their mutual child, the clothing boutique.

Pascale Armand’s Gigi at first introduction is a woman you wouldn’t want to mess with, both volatile and armored. But as we get to know her, Gigi reveals her fragility and ultimately shows great strength in her vulnerability. It’s an affecting arc of character and Armand seems to inhabit it rather than perform it.

As Pita, Jude Tibeau uses his versatile baritone voice and sinuous body to create a character on stage that seems to shape-shift as we watch him. His Pita can be in one moment joyously, outrageously camp and in another abused, defeated and then suddenly fiercely resilient. He reminded me a bit of a young Geoffrey Holder.

I was at a matinee performance and though the crowd was older it was a diverse older crowd. At one moment in the play when Gigi defends the Haitian people by declaring proudly that they make up their own rules because they have always had to, there was a burst of applause from a section of the audience. That applause acknowledged Haiti’s role as the first black colonized nation to seize its own independence. But perhaps it also acknowledged the historical price of that independence and the present horrific crisis that Haiti is going through.

The Haiti of Morisseau’s play however is in pleasant soft focus. It seems to be taking place in a relatively stable country with functioning airports, international trade and the presence of neoliberal NGO’s. There is a bit of a Disney quality to it which, frankly, came as a bit of a relief. To capture the present moment might require the Plutonian vision of a writer like Roberto Bollaño, but then much of the present world might. That said, in Morisseau’s play the layers of past and present violence, chaos and exploitation are fully present.

The scenic design by Jason Sherwood stages the play on a revolving set which turns to reveal the interior and exterior of Gigi’s jewel-hued boutique and one other location. The revolving set sits underneath a multi-hued proscenium representing the hillside shacks of Port-au-Prince. The costume design by Haydee Zelideth is equally brilliantly colored and is a constant visual treat. Casting for the production is by Sujotta Pace.